Before I begin, I need to admit that my game-in-progress has not yet been played yet. I understand this is a criminal offense, so I will accept the necessary punishments. My game prototype, PEACE, was only a thought in my head last week (I hadn’t come to class with a game idea yet), and I wanted to give myself proper time to think of a game idea I could be passionate about.

Because of these circumstances, this blog post will be in part a description of PEACE and also a play log of the other two games I’ve played so far from two other game developers.

PEACE is Mad Libs meets LA Noire, meets telephone. There are two roles: the suspect(s), and the investigator. The suspects know, either in whole (one suspect) or parts (multiple suspects), the entire story of the crime–and the investigator’s role is to figure out who’s innocent and who’s guilty.

At the beginning of the game, the investigator is chosen and walks out of the room, as the suspect(s) come up with the story of the original crime. The suspect(s) are given a story template, similar to something you’d see in Mad Libs, where they fill out the blanks to the story. If there is more than one suspect, the template is split into sections, filled out individually (and in private) by each suspect. In these scenarios, no one person knows the full story (that is, until the investigator finds it all out). For three plus player games, the templates are made such that there are one or more criminals (The template tells the suspects each privately if they’re innocent or a criminal).

If in a two player game, the suspect will be either innocent or a criminal.

The investigator returns after the template is completed, and is given some basic facts about the crime (date, time, location, what crime). The investigator can choose whomever suspect to question first. The investigator is allowed to ask three yes-or-no questions to that suspect. The suspect in turn must tell the truth to two of the questions, and can lie to one of them. The suspect decides which one of the three answers to be a lie. If the investigator asks if they’re a/the criminal, the suspect is allowed to lie an extra time, if need be. After the questioning is done, the investigator must pick another suspect, and do another set of three yes-or-no questions to that suspect. This continues until all suspects have been questioned, and the questioning phase ends.

If there is only one suspect, the investigator can ask five yes-or-no questions before the accusation phase.

With the evidence gathered, the investigator will choose one suspect and accuse them as a criminal, or pardon them as an innocent. The suspect will tell the truth. If accusing and the suspect is a criminal, they are “locked away” and are out of the game. If accusing and the suspect is innocent, the investigator takes a “hit” by one to their credibility meter, which starts at a number equal to half the number of players (rounded down for odd numbers). If pardoning and the suspect is a criminal, the investigator takes a “hit” to their credibility meter, and if pardoning an innocent, that player is acquitted and are out of the game.

If playing with one suspect, there is only one round of the game; if the suspect is a criminal and is correctly accused, the investigator wins.

The game continues swapping between questioning and accusation until either all players have been locked away or acquitted (the investigator/innocents win), or the investigator’s credibility meter drops to zero (the criminals win).

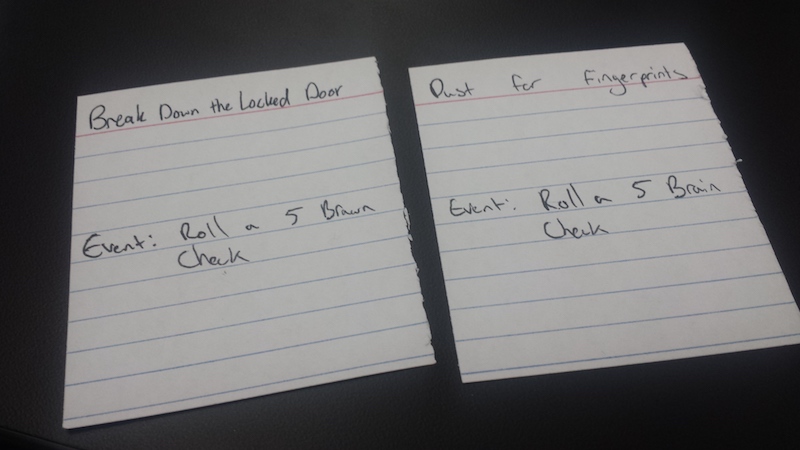

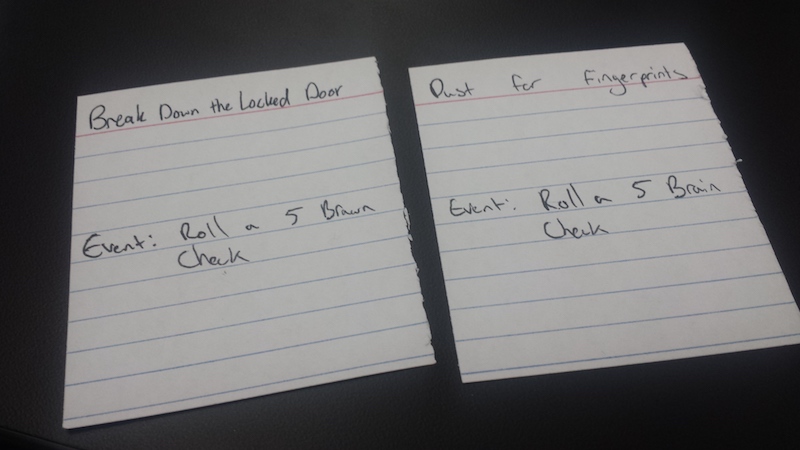

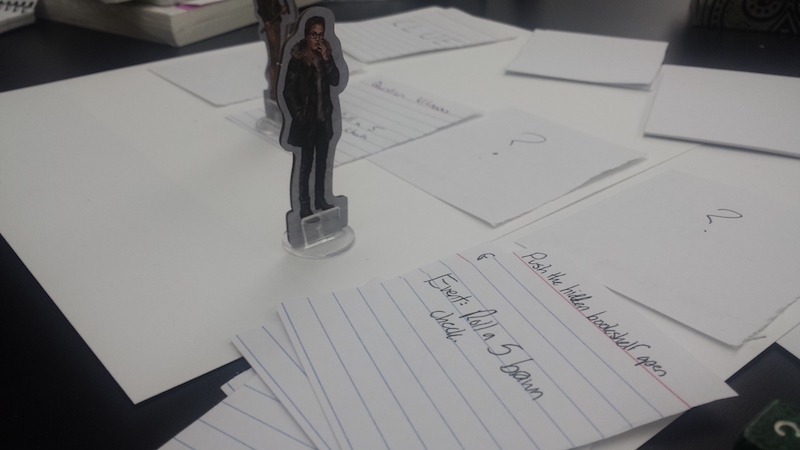

The first game I played (which was not mine) was a Sherlock Holmes-esque mystery solving game, involving a “brains” oriented character (Sherlock), and a “brawns” character (Dr. Watson). In the first iteration, the game was curated on the basis of the “luck of the draw” mechanic. Players would iterate through cards in a deck, hoping to find the clue cards, and handle any happening/event cards that were drawn. The game relied on the deck of events and clues, player pieces, player cards with stats, and a general board to place everything in their proper places.

Our first playthrough went like this (D and me, J):

D chose the Sherlock character, I chose Watson. We chose a mystery from the map to solve, and then set up the main “game deck”. D pulled his first card, which was a brain event card where he had to roll 5 or higher. He rolled his d6, and passed. The game passed on to me, where I picked up a card from the deck–it was a brawn event card, I had to roll a 5 or higher. I rolled my d6, and failed. Now it was D’s turn.

This went back and forth until we got through the deck and found the neccessary three “clue” cards, meaning we solved that specific mystery. But we both knew that continually pulling cards from a deck was too boring to continue, so we stopped and revised the gameplay.

In the newly edited version, instead of continually from the deck, we spread out the top 5 cards from the deck across the table, and gave the players the option to choose which card to flip. We hoped giving the players the choosing option could lead to more interesting gameplay.

Here’s our second playthrough:

D and I kept the same characters, but I started first this time, choosing our mystery and, after shuffling the deck and dispersing the top five cards, flipping the far left card over. A clue! Wow, that was fast. We put the clue card aside and replace the spot with a new card from the deck. D’s turn: he chooses the third card from the five, and it’s a brawn check (5 or above). He rolls, and fails. Now my turn. I pick the fifth card and flip it over: a brawn check. I roll and pass. D’s turn again. He tries to get past the card he flipped previously, and rolls his dice again. Another fail.

We continue playing until we find the three clue cards, and quit there. We agreed that while giving the player to choose the card to flip was a nice touch in interactivity, there wasn’t enough that the player was actually choosing to influence the game; it was all based on chance, either by the die or the deck. The class session ended before we were able to come up with a new plan, so hopefully D worked out the kinks in his game.

Onto Jurassic Measures, with C.

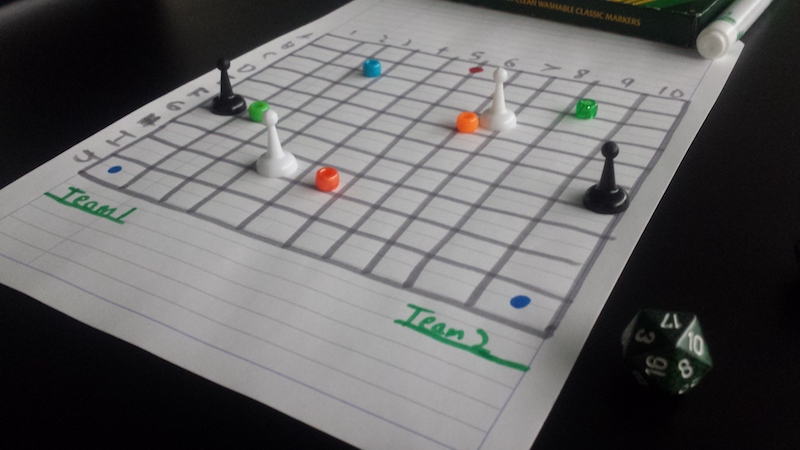

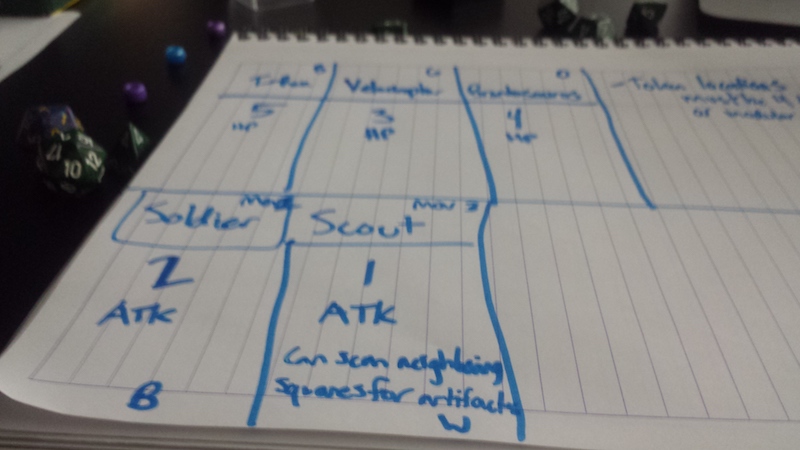

C had formulated Jurassic Measures, a Risk-like board game based in the infamous Jurassic Park dinosaur theme park, last week with another partner. Its basis is the two players are competing to “catch” the most dinosaurs, by fighting them until they reach low HP and then relocating them to the base at the top of the map, or by using traps and attacking other players while they are relocating a dino. There’s also artifacts that can be found and dug up, which are worth points. The game’s inventory consisted of: game pieces for each dino type (the colored beads), game pieces for each player unit type (the pawn pieces), a 10x10 grid map, a d10 for rolling dino placement, and a d6 for sabotage checks.

C gave me the gist of how the game was to be played at the beginning of class, and from there we dived into further refining the details (dinosaur/player unit/artifact types, digging, sabotaging/trap laying, etc). Here’s our playthrough after detail refinement:

We set up the game environment by five dinos being randomly placed in the 10x10 grid map; random being we roll a d10 for the x and y of each dino. C and I start with two player units: the soldier (black pawn) and scout (white pawn). The game begins by me moving my soldier unit two spaces up, and my scout unit three (the soldier can move up to two spaces per turn, the scout three). C follows a similar pattern and moves his two units up. It’s my turn now, so I moved my units so that they both neighbor the same dinosaur, a brontosaurus with 4 hp.

The turn goes back to C, who tells his scout to dig in the neighboring area (a unique move to the scout unit; normally player units can only dig on the spaces they’re on) and finds an artifact. He moves his soldier a few more spaces to the dino nearby him, a velociraptor with 3 hp. In my turn, I attack the brontosaurus with both my units, damaging it by 3 giving it a new hp of 1 (2 from the soldier, 1 from the scout). C attacks the velociraptor with the soldier, damaging by 2 and giving it a new hp of 1 while his scout moves towards me. I attack my brontosaurus with my soldier, setting its hp to 0 allowing me to pick it up for relocating. I do so by picking up the dino with my scout and moving the two towards the base.

At this point we ran out of time for further gameplay, but ended with a conclusion that the artifact digging mechanic needed further detailing. At the time we arbitrarily chose C to find an artifact at the location he dug, but our vision was to give the player a very low chance of finding artifacts (without needing to roll something crazy like d100 dice). That problem we couldn’t find a resolution for at the time, but we did agree to a new set of dinosaur “wave spawning” as an alternative to the more boring “all at once” spawn.